Virginia And Kentucky Resolutions Significance

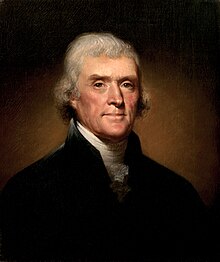

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued that usa had the correct and the duty to declare unconstitutional those acts of Congress that the Constitution did non authorize. In doing so, they argued for states' rights and strict construction of the Constitution. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798 were written secretly by Vice President Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, respectively.

The principles stated in the resolutions became known as the "Principles of '98". Adherents argued that u.s. could approximate the constitutionality of fundamental government laws and decrees. The Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 argued that each individual state has the power to declare that federal laws are unconstitutional and void. The Kentucky Resolution of 1799 added that when usa decide that a constabulary is unconstitutional, nullification by the states is the proper remedy. The Virginia Resolutions of 1798 refer to "interposition" to express the thought that united states of america have a right to "interpose" to prevent harm caused by unconstitutional laws. The Virginia Resolutions contemplated articulation action by u.s..

The Resolutions were produced primarily as campaign cloth for the 1800 United States presidential election and had been controversial since their passage, eliciting disapproval from 10 state legislatures. Ron Chernow assessed the theoretical impairment of the resolutions as "deep and lasting ... a recipe for disunion".[1] George Washington was so appalled by them that he told Patrick Henry that if "systematically and pertinaciously pursued", they would "dissolve the wedlock or produce coercion".[1] Their influence reverberated correct up to the Civil War and beyond.[2] In the years leading upwards to the Nullification Crisis, the resolutions divided Jeffersonian democrats, with states' rights proponents such every bit John C. Calhoun supporting the Principles of '98 and President Andrew Jackson opposing them. Years later on, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 led anti-slavery activists to quote the Resolutions to back up their calls on Northern states to nullify what they considered unconstitutional enforcement of the law.[three]

Provisions of the Resolutions [edit]

The resolutions opposed the federal Conflicting and Sedition Acts, which extended the powers of the federal government. They argued that the Constitution was a "meaty" or agreement among the states. Therefore, the federal government had no right to exercise powers not specifically delegated to it. If the federal government assumed such powers, its acts could be declared unconstitutional by us. And so, states could decide the constitutionality of laws passed by Congress. Kentucky'due south Resolution i stated:

That the several states composing the United States of America are not united on the principle of unlimited submission to their general government; but that, past compact, under the style and title of a Constitution for the United States, and of amendments thereto, they constituted a general government for special purposes, delegated to that government certain definite powers, reserving, each state to itself, the residuary mass of right to their own self-regime; and that whensoever the full general authorities assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force; that to this meaty each state acceded as a state, and is an integral party, its co-States forming, as to itself, the other party; that this authorities, created by this compact, was non made the exclusive or terminal guess of the extent of the powers delegated to itself, since that would have made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers; simply that, as in all other cases of meaty among powers having no common guess, each party has an equal right to guess for itself, too of infractions as of the mode and measure of redress.

A key provision of the Kentucky Resolutions was Resolution 2, which denied Congress more than a few penal powers by arguing that Congress had no dominance to punish crimes other than those specifically named in the Constitution. The Alien and Sedition Acts were asserted to exist unconstitutional, and therefore void, because they dealt with crimes not mentioned in the Constitution:

That the Constitution of the United states, having delegated to Congress a power to punish treason, counterfeiting the securities and electric current coin of the United States, piracies, and felonies committed on the high seas, and offenses against the law of nations, and no other crimes, whatever; and it being true as a full general principle, and 1 of the amendments to the Constitution having also declared, that "the powers non delegated to the United States past the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to u.s. respectively, or to the people," therefore the act of Congress, passed on the 14th day of July, 1798, and intitled "An Act in addition to the deed intitled An Human activity for the punishment of certain crimes against the United States," equally as well the human action passed past them on the—day of June, 1798, intitled "An Human action to punish frauds committed on the bank of the The states," (and all their other acts which assume to create, define, or punish crimes, other than those then enumerated in the Constitution,) are birthday void, and of no force whatsoever.

The Virginia Resolution of 1798 as well relied on the meaty theory and asserted that the states have the right to make up one's mind whether actions of the federal government exceed constitutional limits. The Virginia Resolution introduced the idea that the states may "interpose" when the federal government acts unconstitutionally, in their stance:

That this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that information technology views the powers of the federal regime equally resulting from the meaty to which us are parties, equally limited by the plain sense and intention of the musical instrument constituting that compact, as no further valid than they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that, in example of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, non granted by the said compact, the states, who are parties thereto, have the correct, and are in duty bound, to interpose, for absorbing the progress of the evil, and for maintaining, within their respective limits, the government, rights and liberties, appertaining to them.

History of the Resolutions [edit]

There were ii sets of Kentucky Resolutions. The Kentucky state legislature passed the first resolution on Nov 16, 1798 and the second on December 3, 1799. Jefferson wrote the 1798 Resolutions. The author of the 1799 Resolutions is non known with certainty.[four] Both resolutions were stewarded by John Breckinridge who was falsely believed to have been their author.[5]

James Madison wrote the Virginia Resolution. The Virginia state legislature passed it on December 24, 1798.

The Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 stated that acts of the national government beyond the scope of its constitutional powers are "unauthoritative, void, and of no force". While Jefferson's typhoon of the 1798 Resolutions had claimed that each country has a right of "nullification" of unconstitutional laws,[6] that language did not appear in the final form of those Resolutions. Rather than purporting to nullify the Conflicting and Sedition Acts, the 1798 Resolutions chosen on the other states to join Kentucky "in declaring these acts void and of no strength" and "in requesting their repeal at the next session of Congress".

The Kentucky Resolutions of 1799 were written to respond to u.s. who had rejected the 1798 Resolutions. The 1799 Resolutions used the term "nullification", which had been deleted from Jefferson's draft of the 1798 Resolutions, resolving: "That the several states who formed [the Constitution], being sovereign and independent, have the unquestionable right to guess of its infraction; and, That a nullification, by those sovereignties, of all unauthorized acts done nether colour of that musical instrument, is the rightful remedy." The 1799 Resolutions did not assert that Kentucky would unilaterally turn down to enforce the Alien and Sedition Acts. Rather, the 1799 Resolutions declared that Kentucky "will bow to the laws of the Union" but would continue "to oppose in a constitutional manner" the Alien and Sedition Acts. The 1799 Resolutions ended by stating that Kentucky was entering its "solemn protestation" against those Acts.

The Virginia Resolution did not refer to "nullification", but instead used the thought of "interposition" by u.s.. The Resolution stated that when the national government acts beyond the scope of the Constitution, the states "have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose, for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining, within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties, appertaining to them". The Virginia Resolution did not indicate what form this "interposition" might take or what effect it would take. The Virginia Resolutions appealed to the other states for agreement and cooperation.

Numerous scholars (including Koch and Ammon) take noted that Madison had the words "void, and of no force or effect" excised from the Virginia Resolutions before adoption. Madison afterwards explained that he did this because an individual state does not have the right to declare a federal police zippo and void. Rather, Madison explained that "interposition" involved a collective action of the states, not a refusal past an private state to enforce federal law, and that the deletion of the words "void, and of no forcefulness or effect" was intended to make clear that no individual state could nullify federal law.[7]

The Kentucky Resolutions of 1799, while claiming the right of nullification, did not assert that individual states could exercise that correct. Rather, nullification was described as an action to exist taken by "the several states" who formed the Constitution. The Kentucky Resolutions thus ended up proposing joint action, every bit did the Virginia Resolution.[8]

The Resolutions joined the foundational beliefs of Jefferson's party and were used equally political party documents in the 1800 election. As they had been shepherded to passage in the Virginia Firm of Delegates by John Taylor of Caroline,[9] they became role of the heritage of the "Old Republicans". Taylor rejoiced in what the Business firm of Delegates had made of Madison'due south draft: it had read the claim that the Conflicting and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional every bit meaning that they had "no forcefulness or effect" in Virginia—that is, that they were void. Future Virginia Governor and U.S. Secretary of State of war James Barbour concluded that "unconstitutional" included "void, and of no strength or upshot", and that Madison's textual change did not touch on the pregnant. Madison himself strongly denied this reading of the Resolution.[10]

The long-term importance of the Resolutions lies not in their attack on the Alien and Sedition Acts, simply rather in their stiff statements of states' rights theory, which led to the rather different concepts of nullification and interposition.

Responses of other states [edit]

The resolutions were submitted to the other states for approving, but with no success. Seven states formally responded to Kentucky and Virginia by rejecting the Resolutions[11] and three other states passed resolutions expressing disapproval,[12] with the other 4 states taking no action. No other state affirmed the resolutions. At least six states responded to the Resolutions by taking the position that the constitutionality of acts of Congress is a question for the federal courts, non the state legislatures. For case, Vermont's resolution stated: "It belongs non to state legislatures to decide on the constitutionality of laws made past the general government; this power existence exclusively vested in the judiciary courts of the Union."[xiii] In New Hampshire, newspapers treated them every bit military threats and replied with foreshadowings of civil war. "We think it highly probable that Virginia and Kentucky volition be sadly disappointed in their infernal program of heady insurrections and tumults," proclaimed ane. The country legislature'south unanimous answer was blunt:

Resolved, That the legislature of New Hampshire unequivocally express a business firm resolution to maintain and defend the Constitution of the United States, and the Constitution of this state, confronting every aggression, either foreign or domestic, and that they will support the government of the Usa in all measures warranted by the former. That the state legislatures are not the proper tribunals to decide the constitutionality of the laws of the general government; that the duty of such determination is properly and exclusively confided to the judicial section.[14]

Alexander Hamilton, then building up the army, suggested sending it into Virginia, on some "obvious pretext". Measures would exist taken, Hamilton hinted to an marry in Congress, "to act upon the laws and put Virginia to the Test of resistance".[15] At the Virginia General Assembly, delegate John Mathews was said to have objected to the passing of the resolutions past "tearing them into pieces and trampling them underfoot."[16]

The Study of 1800 [edit]

In January 1800, the Virginia General Associates passed the Report of 1800, a document written by Madison to respond to criticism of the Virginia Resolution by other states. The Report of 1800 reviewed and affirmed each part of the Virginia Resolution, affirming that us have the correct to declare that a federal action is unconstitutional. The Written report went on to assert that a announcement of unconstitutionality by a state would be an expression of opinion, without legal event. The purpose of such a declaration, said Madison, was to mobilize public stance and to arm-twist cooperation from other states. Madison indicated that the power to make bounden constitutional determinations remained in the federal courts:

Information technology has been said, that information technology belongs to the judiciary of the United States, and not the state legislatures, to declare the meaning of the Federal Constitution. ... [T]he declarations of [the citizens or the land legislature], whether affirming or denying the constitutionality of measures of the Federal Government ... are expressions of opinion, unaccompanied with whatever other effect than what they may produce on stance, by exciting reflection. The expositions of the judiciary, on the other hand, are carried into immediate outcome by force. The onetime may atomic number 82 to a change in the legislative expression of the general will; possibly to a change in the opinion of the judiciary; the latter enforces the general will, whilst that will and that opinion continue unchanged.[17]

Madison then argued that a state, after declaring a federal police unconstitutional, could take action past communicating with other states, attempting to enlist their support, petitioning Congress to repeal the police force in question, introducing amendments to the Constitution in Congress, or calling a constitutional convention.

Withal, in the aforementioned document Madison explicitly argued that the states retain the ultimate power to decide near the constitutionality of the federal laws, in "extreme cases" such as the Alien and Sedition Deed. The Supreme Courtroom can decide in the final resort only in those cases which pertain to the acts of other branches of the federal authorities, but cannot takeover the ultimate decision-making power from united states of america which are the "sovereign parties" in the Constitutional meaty. Co-ordinate to Madison states could override non but the Congressional acts, simply as well the decisions of the Supreme Courtroom:

- The resolution supposes that unsafe powers, not delegated, may not merely be usurped and executed by the other departments, simply that the judicial section, also, may practice or sanction dangerous powers across the grant of the Constitution; and, consequently, that the ultimate right of the parties to the Constitution, to judge whether the compact has been dangerously violated, must extend to violations past ane delegated authority also as by another—by the judiciary likewise as by the executive, or the legislature.

- Even so true, therefore, it may exist, that the judicial section is, in all questions submitted to it by the forms of the Constitution, to decide in the terminal resort, this resort must necessarily exist deemed the terminal in relation to the authorities of the other departments of the authorities; non in relation to the rights of the parties to the ramble compact, from which the judicial, also as the other departments, concord their delegated trusts. On whatever other hypothesis, the delegation of judicial ability would counteract the dominance delegating it; and the concurrence of this section with the others in usurped powers, might subvert forever, and beyond the possible accomplish of whatever rightful remedy, the very Constitution which all were instituted to preserve.[18]

Madison later strongly denied that individual states have the right to nullify federal police.[nineteen]

Influence of the Resolutions [edit]

Although the New England states rejected the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions in 1798–99, several years subsequently, the state governments of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island threatened to ignore the Embargo Act of 1807 based on the authorization of states to stand to laws deemed by those states to be unconstitutional. Rhode Island justified its position on the embargo act based on the explicit linguistic communication of interposition. Nonetheless, none of these states actually passed a resolution nullifying the Embargo Act. Instead, they challenged information technology in court, appealed to Congress for its repeal, and proposed several constitutional amendments.

Several years afterward, Massachusetts and Connecticut asserted their right to test constitutionality when instructed to send their militias to defend the coast during the War of 1812. Connecticut and Massachusetts questioned some other embargo passed in 1813. Both states objected, including this statement from the Massachusetts legislature, or General Courtroom:

A ability to regulate commerce is abused, when employed to destroy it; and a manifest and voluntary abuse of ability sanctions the right of resistance, as much as a straight and palpable usurpation. The sovereignty reserved to the states, was reserved to protect the citizens from acts of violence by the United States, as well as for purposes of domestic regulation. We spurn the thought that the complimentary, sovereign and contained State of Massachusetts is reduced to a mere municipal corporation, without ability to protect its people, and to defend them from oppression, from whatever quarter it comes. Whenever the national compact is violated, and the citizens of this State are oppressed past savage and unauthorized laws, this Legislature is leap to interpose its power, and wrest from the oppressor its victim.[20]

Massachusetts and Connecticut, along with representatives of some other New England states, held a convention in 1814 that issued a statement asserting the correct of interposition. But the argument did not endeavour to nullify federal constabulary. Rather, it made an entreatment to Congress to provide for the defense of New England and proposed several ramble amendments.

The Nullification Crisis [edit]

During the "nullification crisis" of 1828–1833, S Carolina passed an Ordinance of Nullification purporting to nullify 2 federal tariff laws. South Carolina asserted that the Tariff of 1828 and the Tariff of 1832 were beyond the authority of the Constitution, and therefore were "null, void, and no law, nor binding upon this State, its officers or citizens". Andrew Jackson issued a declaration confronting the doctrine of nullification, stating: "I consider ... the ability to counteract a police force of the United States, assumed past one Country, incompatible with the being of the Wedlock, contradicted expressly past the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed." He also denied the right to secede: "The Constitution ... forms a government not a league. ... To say that any Country may at pleasance secede from the Union is to say that the United States is not a nation."[21]

James Madison likewise opposed S Carolina'southward position on nullification. Madison argued that he had never intended his Virginia Resolution to suggest that each individual state had the power to nullify an human activity of Congress. Madison wrote: "But information technology follows, from no view of the subject, that a nullification of a law of the U. S. tin can as is now contended, vest rightfully to a single State, as one of the parties to the Constitution; the State not ceasing to avow its adherence to the Constitution. A plainer contradiction in terms, or a more than fatal inlet to anarchy, cannot be imagined." Madison explained that when the Virginia Legislature passed the Virginia Resolution, the "interposition" it contemplated was "a concurring and cooperating interposition of the States, not that of a single State. ... [T]he Legislature expressly disclaimed the thought that a declaration of a State, that a law of the U. S. was unconstitutional, had the effect of annulling the constabulary."[xix] Madison went on to argue that the purpose of the Virginia Resolution had been to arm-twist cooperation by the other states in seeking change through ways provided in the Constitution, such as amendment.

The compact theory [edit]

The Supreme Court rejected the compact theory in several nineteenth century cases, undermining the basis for the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions. In cases such equally Martin v. Hunter's Lessee,[22] McCulloch v. Maryland,[23] and Texas v. White,[24] the Court asserted that the Constitution was established directly past the people, rather than being a compact among the states. Abraham Lincoln likewise rejected the meaty theory proverb the Constitution was a binding contract among the states and no contract tin be changed unilaterally by one political party.

School desegregation [edit]

In 1954, the Supreme Court decided Brown 5. Board of Education, which ruled that segregated schools violate the Constitution. Many people in southern states strongly opposed the Dark-brown decision. James J. Kilpatrick, an editor of the Richmond News Leader, wrote a serial of editorials urging "massive resistance" to integration of the schools. Kilpatrick, relying on the Virginia Resolution, revived the idea of interposition by united states of america every bit a ramble basis for resisting federal government activity.[25] A number of southern states, including Arkansas, Louisiana, Virginia, and Florida, subsequently passed interposition and nullification laws in an effort to preclude integration of their schools.

In the case of Cooper v. Aaron,[26] the Supreme Court unanimously rejected Arkansas' attempt to use nullification and interposition. The Supreme Court held that nether the Supremacy Clause, federal law was decision-making and united states of america did not have the power to evade the application of federal constabulary. The Courtroom specifically rejected the contention that Arkansas' legislature and governor had the power to nullify the Brown decision.

In a like example arising from Louisiana's interposition deed, Bush 5. Orleans Parish School Lath,[27] the Supreme Court affirmed the determination of a federal district court that rejected interposition. The commune court stated: "The conclusion is articulate that interposition is not a constitutional doctrine. If taken seriously, it is illegal disobedience of constitutional authority. Otherwise, 'it amounted to no more than than a protest, an escape valve through which the legislators blew off steam to relieve their tensions.' ... Withal solemn or spirited, interposition resolutions have no legal efficacy."[28]

Importance of the Resolutions [edit]

Merrill Peterson, Jefferson's otherwise very favorable biographer, emphasizes the negative long-term bear on of the Resolutions, calling them "unsafe" and a production of "hysteria":

Called along by oppressive legislation of the national government, notably the Alien and Sedition Laws, they represented a vigorous defence of the principles of freedom and self-government under the United States Constitution. But since the defense involved an appeal to principles of state rights, the resolutions struck a line of argument potentially as dangerous to the Union as were the odious laws to the liberty with which information technology was identified. Ane hysteria tended to produce another. A crisis of freedom threatened to become a crunch of Spousal relationship. The latter was deferred in 1798–1800, but it would return, and when it did the principles Jefferson had invoked confronting the Alien and Sedition Laws would sustain delusions of state sovereignty fully every bit violent as the Federalist delusions he had combated.[29]

Jefferson'southward biographer Dumas Malone argued that the Kentucky resolution might have gotten Jefferson impeached for treason, had his actions become known at the time.[30] In writing the Kentucky Resolutions, Jefferson warned that, "unless arrested at the threshold", the Alien and Sedition Acts would "necessarily drive these states into revolution and blood." Historian Ron Chernow says of this "he wasn't calling for peaceful protests or civil disobedience: he was calling for outright rebellion, if needed, confronting the federal regime of which he was vice president." Jefferson "thus fix forth a radical doctrine of states' rights that effectively undermined the constitution."[1] Chernow argues that neither Jefferson nor Madison sensed that they had sponsored measures as inimical equally the Alien and Sedition Acts themselves.[1] Historian Garry Wills argued "Their nullification effort, if others had picked it upwards, would have been a greater threat to liberty than the misguided [alien and sedition] laws, which were soon rendered feckless by ridicule and electoral pressure".[31] The theoretical impairment of the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions was "deep and lasting, and was a recipe for disunion".[1] George Washington was and then appalled past them that he told Patrick Henry that if "systematically and pertinaciously pursued", they would "dissolve the union or produce coercion".[1] The influence of Jefferson's doctrine of states' rights reverberated right up to the Civil War and beyond.[2] Future president James Garfield, at the close of the Ceremonious State of war, said that Jefferson's Kentucky Resolution "contained the germ of nullification and secession, and we are today reaping the fruits".[2]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Chernow, Ron. "Alexander Hamilton". 2004. p587. Penguin Press.

- ^ a b c Knott. "Alexander Hamilton and the Persistence of Myth". p48

- ^ Run into Unconstitutionality of the Avoiding Act, past Byron Paine (1854).

- ^ See Powell, H. Jefferson, "The Principles of '98: An Essay in Historical Retrieval", 80 Virginia Police force Review 689, 705 n.54 (1994).

- ^ "The Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 | The Papers of Thomas Jefferson". jeffersonpapers.princeton.edu . Retrieved 2020-05-05 .

- ^ Jefferson's typhoon said: "where powers are assumed [by the federal regime] which accept not been delegated, a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy: that every State has a natural right in cases non within the compact, (casus non fœderis) to nullify of their own dominance all assumptions of power past others within their limits." See Jefferson'due south draft of the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798.

- ^ Madison, James, "Notes, On Nullification", Library of Congress, December, 1834. Meet Powell, "The Principles of '98: An Essay in Historical Retrieval", fourscore Virginia Police force Review at 718 (the Virginia resolutions "did non in fact license any legally significant activity by an individual state. The authority of united states of america over the Constitution and its interpretation was collective and could be exercised just in concert through the electoral process or past a quasi-revolutionary act of the people themselves").

- ^ Run into Powell, "The Principles of '98: An Essay in Historical Retrieval", 80 Virginia Law Review at 719-720 & n.123 ("when the Resolutions of 1799 declared that 'nullification' was 'the rightful remedy' for federal overreaching, the legislature carefully ascribed this remedy to the states collectively, thus equating its position with that of Madison and the Virginia Resolutions. ... The Resolutions implicitly conceded that the state'southward private means of resisting the Acts were political in nature.").

- ^ Taylor, Jeff (2010-07-01) States' Fights Archived 2012-09-11 at archive.today, The American Conservative

- ^ Madison, James, "Notes, On Nullification", Library of Congress, December, 1834.

- ^ The seven states that transmitted formal rejections were Delaware, Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Meet Elliot, Jonathan (1907) [1836]. . Vol. four (expanded second ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott. pp. 538–539. ISBN0-8337-1038-ix.

- ^ Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Bailiwick of jersey passed resolutions that disapproved the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions, but these states did non transmit formal responses to Kentucky and Virginia. Anderson, Frank Maloy (1899). . American Historical Review. pp. 45–63, 225–244.

- ^ Elliot, Jonathan (1907) [1836]. . . Vol. four (expanded second ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott. pp. 538–539. ISBN0-8337-1038-nine. . The other states taking the position that the constitutionality of federal laws is a question for the federal courts, not us, were New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania. The Governor of Delaware also took this position. Anderson, Frank Maloy (1899). . American Historical Review. pp. 45–63, 225–244.

- ^ Elliot, Jonathan (1907) [1836]. . . Vol. 4 (expanded 2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott. pp. 538–539. ISBN0-8337-1038-9.

- ^ Feb two, 1799, Hamilton Papers vol 22 pp 452–53.

- ^ Rice, Otis K. 1986. A History of Greenbrier County. Greenbrier Historical Society, p. 222

- ^ Report of 1800, http://www.constitution.org/rf/vr_1799.htm

- ^ "Federal v. Consolidated Government: James Madison, Study on the Virginia Resolutions". Printing-pubs.uchicago.edu. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Madison, James "Notes, On Nullification", Library of Congress, Dec, 1834.

- ^ The General Court of Massachusetts on the Embargo, February 22, 1814

- ^ "President Jackson's Annunciation Regarding Nullification, December 10, 1832". Yale Police force School. Retrieved 2009-05-eleven .

- ^ Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, fourteen U.Due south. (one Wheat.) 304 (1816)

- ^ McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (four Wheat.) 316 (1819)

- ^ Texas v. White, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 700 (1869)

- ^ "Obituary: James J. Kilpatrick / Conservative columnist sparred on 'threescore Minutes'". Pittsburgh Mail service-Gazette. Baronial 17, 2010.

- ^ Cooper 5. Aaron, 358 U.South. 1 (1958)

- ^ Bush-league 5. Orleans Parish School Board, 364 U.South. 500 (1960)

- ^ Bush-league v. Orleans Parish Schoolhouse Board, 188 F. Supp. 916 (E.D. La. 1960), aff'd 364 U.S. 500 (1960)

- ^ Peterson, Merrill (1975). Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography. Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-19-501909-iv.

- ^ Chernow, Ron. "Alexander Hamilton". 2004. p586. Penguin Press.

- ^ Wills, Gary. "James Madison". p49

Further reading [edit]

- Anderson, Frank Maloy (1899). . American Historical Review. pp. 45–63, 225–244.

- Bird, Wendell. "Reassessing Responses to the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions: New Testify from the Tennessee and Georgia Resolutions and from Other States," Journal of the Early Republic 35#four (Winter 2015)

- Elkins, Stanley; Eric McKitrick (1994). The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800 . Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN978-0-19-509381-0.

- Gutzman, Kevin, "'O, What a Tangled Spider web We Weave ... ': James Madison and the Compound Republic", Continuity 22 (1998), nineteen–29.

- Gutzman, Kevin, "A Troublesome Legacy: James Madison and the 'Principles of '98,'" Journal of the Early Republic 15 (1995), 569–89.

- Gutzman, Kevin., "The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions Reconsidered: 'An Appeal to the _Real Laws_ of Our State,'" Journal of Southern History 66 (2000), 473–96.

- Koch, Adrienne; Harry Ammon (1948). "The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions: An Episode in Jefferson's and Madison'south Defense of Ceremonious Liberties". The William and Mary Quarterly. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 5 (2): 145–176. doi:ten.2307/1917453. JSTOR 1917453.

- Koch, Adrienne (1950). Jefferson and Madison: The Great Collaboration. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN978-1-56852-501-iii.

- Watkins, William (2004). Reclaiming the American Revolution: the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions and their Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN978-1-4039-6303-1.

External links [edit]

![]()

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Text of the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798

- Text of Virginia Resolutions of 1798

- Answers from Delaware, Rhode Isle, Massachusetts, New York (likewise to Kentucky), Connecticut, New Hampshire (likewise to Kentucky), and Vermont.

- Text of the Kentucky Resolutions of 1799

- James Madison, Report on the Virginia Resolutions

- The Accost of the Minority in the Virginia Legislature to the People of that State, Containing a Vindication of the Constitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Laws (1799)

Virginia And Kentucky Resolutions Significance,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kentucky_and_Virginia_Resolutions

Posted by: stantonsittoss.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Virginia And Kentucky Resolutions Significance"

Post a Comment